People like to talk

One of the consequences of the Iron Curtain was that people in societies on both sides had very stereotypical and false images of the “other” societies. False or misleading propaganda played its part. Restricting communication through all forms of media – newspapers, radio and television – also served to seal off societies from each other. Travel between them was effectively impossible, other than for a privileged few, and even then controls and fears of reprisals prevented any deep and open interchanges. The only way to get to know another society is simply to go there and just wander about. But only after 1989 did that become possible.

An Irish economist in Bulgaria

In the course of my work as an economist, I have had the opportunity of visiting Bulgaria over the past decade. Until this Spring, I never moved outside Sofia, and it was this bustling and dynamic city that served to form my impressions of the country. My work deals with the Structural Funds made available by the European Union to prepare candidate states for membership, and to assist in accelerating their development when they join. So I came to know Bulgaria through dry economic statistics, in terms of its stage of post-Communist transition, the broad structure of its rapidly evolving economy, its trade relationships with neighbours, the competition with its closest neighbour – Romania – to which it was often compared.

We economists tend to be somewhat unimaginative people, and probably lack intellectual curiosity. Only in the Spring of this year did I venture outside Sofia, and then only under pressure from my wife, Mary, who accompanied me when I spoke at a conference held in Sofia. Mary planned an itinerary that would take us to the Pirin mountains in the far south and then to the river Danube in the far north. The vivid impressions of that trip introduced me to a side of Bulgaria whose existence I had never expected. It also forced me to reflect on the development of my own country as it made a troubled way from rural underdevelopment to so-called Celtic Tiger prosperity.

We stayed in the village of Banya, nestling in the foothills of the spectacular Pirin mountains. Late in the evening we had a meal in a little family run restaurant in Banya. Based on my experience of similar small villages in Ireland, I was prepared for simplicity, at best, and unattractive stodgy fare, at worst. We still talk about the feast that followed! As well as an array of deliciously roasted meats, the salad was a joy to eat, with ingredients of a freshness that spoke of local produce and recent gathering. This was but the first of a series of wonderful and exciting meals that we had in small towns and villages throughout Bulgaria, and an introduction to Bulgarian cuisine that has changed our appreciation of excellent food.

Very early next morning I wandered through the slowly wakening village and was assailed by sounds that were a dim memory of my childhood, as the farm animals woke up, and wakened the villagers up, to a new day. At the edge of the village, across a flat field, the mountains rose up mysteriously in the background. But alongside the sense of awe before such spectacular beauty, I had the first pangs of worry at the pace of development in Bulgaria, and whether this development risked killing off what makes Bulgaria beautiful and unique.

Our trip to Vidin brought us to the northern end of Bulgaria. It was only when we stood on the ramparts of the castle overlooking the mighty Danube that we really understood the size and complexity of the new Europe that we are creating.

When you live in Ireland, a small island in the Atlantic ocean, the rest of the world is remote and un-threatening. But here in Vidin the Danube flowed slowly down to the Black Sea, linking Bulgaria to the very heart of Europe. And, as if to reinforce the point, the sad and ruined Synagogue in the town gave witness to a less hopeful time in our continent, events that were at the core of the desire to establish a Europe of friendly and cooperating nations that could never go to war again.

One does not have to be in Bulgaria for long to see that it is a society in a hurry to develop and change. The pristine natural beauty of the Pirin mountains, as well as the unspoiled Danube river basin near Vidin, are uneasy bedfellows with the massive tourist-oriented building boom that threatens to damage it irreparably. More generally, a country like Bulgaria, in the early stages of rapid development, runs the risk of undervaluing its natural environment, and trading its protection and enhancement off against the lure of rapid growth.

Tradition and development in Ireland

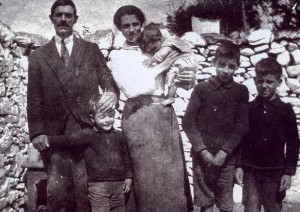

Ireland had a similar experience to the one that Bulgaria is presently undergoing, and my recent trip forced me to revisit my feelings on how development and modernisation has changed my own country. I was born just after WW-2 at a time when Ireland was a poor rural economy, with a weak urban structure. My father grew up in a village called Murrisk, on the western seaboard looking out on the Atlantic Ocean to America, destination of so many Irish emigrants. The one surviving early photograph of his family, taken in 1921, shows a scene outside their cottage (my father is on the extreme right of the picture). As a young child visiting my grandparents in the early 1950’s, the village was so remote that when a car drove through at night, there would be a fireside conversation as to who it might be and why they were here!

Electricity did not come to Murrisk until 1955, and the interiors of the cottages, which had previously been whitewashed to reflect the dim oil lamps, were now covered with ugly, patterned brown wall paper, to welcome the modern age. Behind the cottage lay the spectacular mountain, Croagh Patrick, named after Ireland’s patron saint, with its little chapel on the top. Here, on the last Sunday in July, over 50,000 pilgrims would come to climb the mountain through the night – some barefoot – and we children got to stay up all night, or at least until fatigue conquered us.

Ireland’s development, unlike that of Bulgaria, was of the gradual kind. As children of the modern era, we foolishly despised our rural, Gaelic heritage and lusted after the bright lights of city life. But I fondly recall my grandmother, Sarah, waking me one night and leading me, sleepy-eyed out into the pitch darkness outside the cottage to look up at a spectacular comet, amid the splendors of the Milky Way that are dimmed to children today by the loom of artificial lights.

Our good fortune in Ireland was that we were given a few decades to experience modernity at a time when we did not have the resources to cause irreparable damage to our natural environment. The psychological turning point to the village of Murrisk came in the mid-1980s when gold was discovered in Croagh Patrick. If it had been two decades earlier, the mountain would have been sacrificed and the gold mined. Thankfully, the trade-offs were now understood better, and the transitory benefits of gold were rejected in favour of the enduring protection of the environment.

Can tradition and modernity co-exist?

A relatively poor country is at its most vulnerable when it opens to the forces of globalisation. If that process is gradual, then its institutions have the chance to evolve to cope with the challenges and the crucial trade-offs that are involved. Ireland was very lucky that it opened its economy in the early 1960s, a time when the forces of globalisation were weaker than they are today. Bulgaria faces a more serious challenge. It has had to undergo a transition from the previous regime of Socialism and central planning at the same time as it entered a world where the forces of globalisation are strong and irresistible. Bulgarian internal institutions are still in a state of flux and rapid development, with limited controls, have generated some undesirable consequences.

The Irish experience shows the importance of building institutional strengths at all levels of society. The post-Communist legacy makes that task a particularly difficult one in Bulgaria. The early EU Structural Fund programmes in Ireland included special schemes designed to assist rural groups to organise and take a role in influencing their own communities. For example, there were courses on how to run meetings; how to gather information to support a case; how to listen to the other side of the case; how to build local partnerships. Previous failures in these areas had often made local initiatives ineffective and left the region vulnerable to outside forces. Today, Murrisk (population 300) has its own Development Association, and even has had a series of 5-year Development Plans that it has successfully implemented. Its finances come partially from state aid, but mainly from its own small Lottery. A recent project erected a memorial to the fishermen of the village, and the local Arch Bishop did the honours.

The dream of Murrisk is to win the annual competition for the most beautiful village in Ireland, and each year it makes progress towards that goal. In the 1950s, the aftermath of the annual pilgrimage usually left behind a mountain of litter and debris, and it was left to the Atlantic storms eventually to wash it all away. Today, by the end of Pilgrimage Sunday, the village is pristine. After all, who knows when the Inspector of Beautiful Villages might decide to visit!